I’ve been working on my 90s anime comedy fantasy RPG Dragon World off and on for nearly a decade now, and I really need to finish and publish it, for a variety of reasons. When that’s out of the way I want to do some supplements, including alternate settings. One that I started on a little bit is “El Kazad,” which draws on weirder bits of fantasy like Bastard!! and the Elric stories. I also want to do an Asian fantasy setting, and there’s just no way I’m going to do that on my own. From basically every standpoint I need actual people from those cultures to contribute, because threading the needle between authenticity, colorful fantasy, and comedy is hard enough with things that come from something like my own culture. Needless to say, not everyone cares that much.

TSR put out the Oriental Adventures setting book for AD&D in 1985, and unfortunately it set the bar for Asian settings in TTRPGs in the Anglosphere going forward. I can cut Gygax a little slack simply because it was the 1980s and good information on Asian cultures was harder to come by, but on the other hand it seems stupid that apparently no one at TSR thought to e.g. write to the publishers of the Japanese editions of D&D for assistance. TTRPG books that badly misrepresent other cultures never stopped in the internet age though, and aren’t limited to Asia either. White Wolf’s portrayal of Italian culture with Clan Giovanni in Vampire: The Masquerade is also just plain inaccurate while trivializing the very real threat the Mafia represents to the people of Italy. On top of simply being a poor attempt at portraying Italian culture, the book has a lot of wasted potential. Venice could be a fascinating setting for vampire stories, but you’re not going to get there if you don’t even understand the basic premise of the city enough to know why there wouldn’t be any catacombs there.

I was thinking about this because of the announcement that a Japan-inspired third-party supplement for D&D5e would include “Honor” mechanics. This seems to come almost entirely from the fact that Oriental Adventures had Honor rules, regardless of whether they were any good. Looking at that bit of OA again now, they’re very Gygax, adding yet another number to keep track of and potentially punish the players with. The DM has to go over the events of each session and dole out bonuses and penalties to each PC’s Honor score, as though the game didn’t have enough bookkeeping already. The score creates NPC reaction modifiers, potentially triggers a PC getting rewards if it goes high enough, and if your Honor goes below zero your character is out of the game and “The player should crumple up the character record sheet and toss it away.”

In typically Gygaxian fashion there’s no explanation for what exactly happens when you reach negative Honor. It doesn’t say that the character becomes a pariah or gets executed; it’s as though someone in the Celestial Bureaucracy decides to delete them from the world. While he uses the word “honor,” it’s really more of a reputation system, though the way Gygax wrote the rules, it’s as though some supernatural force is keeping a tally. If your character did something “dishonorable” in a dungeon and no one in the party told a soul about it, by the rules as written the character’s Honor score—their reputation—would suffer somehow. It’s possible to write this off as one of the many abstractions in the game’s rules, but it’s exactly the kind of thing that Gygax wouldn’t deign to explain in the text. I’m sure at least some people actually played D&D games set in Kara-Tur (or Rokugan, in the 3rd Edition version of Oriental Adventures), but I’ve never actually heard any accounts. That leaves me wondering how the Honor mechanics (among other things) worked out in actual play, but looking at it today it doesn’t seem like something that particularly enhances the experience.

Although vanilla D&D has a few classes that have fictionalized chivalric codes to follow, even for the likes of the paladin Gygax didn’t feel the need to give them any sort of reputation system. Whether a paladin is following their code or is going to fall and lose their powers is left up to the DM’s discretion. The Pendragon RPG, which explicitly emulates Arthurian stories, is one of the few TTRPGs I know of that pins such concerns on Western fantasy characters in a mechanical form.

D&D has massively influenced Western fantasy, and Oriental Adventures’ fingerprints are all over Asian fantasy as created by Western nerds. There are a lot of examples, but one that comes to mind is how the Asian book for Werewolf: The Apocalypse was called Hengeyokai: Shapeshifters of the East (which was nowhere near the worst or strangest choice in White Wolf’s Year of the Lotus books), apparently just because OA had hengeyokai as one of the new races it introduced. Honor mechanics are one of OA’s more unfortunate innovations. Aside from the fact that OA’s Kara-Tur setting isn’t supposed to draw solely from Japan and thus people’s ideas about what constitutes “honorable” behavior ought to vary, the entire concept of honorable samurai has a deeply problematic—and surprisingly recent—history.

Julian Kay pointed me to a lengthy but excellent essay on Bushido, which helped me solidify my thoughts on the subject.

Real-life samurai were warrior vassals of Japanese feudal lords. Although they did have swords, in battle they acted more as mounted archers, not unlike the Mongols. (Minus the part about being poised to conquer most of Eurasia.) While they did have moral ideals, in practice a lot of major battles were decided by defections. To the extent that ninjas were real, they were spies and assassins, and the major ninja clans were subsumed into the wider political structures and their power struggles . Samurai were heavily armed and privileged assholes, and the lower classes largely despised them. Despite living in a society with public morals—Buddhism was a state religion for a significant stretch of Japanese history—the samurai were no less inclined to do horrible things and go “fuck you, because I can” than any other powerful men. The Tokugawa shogunate brought about an era of peace however, and the samurai became bureaucrats who put their spare time into the arts and had swords as symbols and heirlooms rather than weapons per se.

The Meiji Era saw the modernization of Japan–Japanese leaders realized just how far behind they were and rushed to catch up with the West–and the removal of the traditional class system. While there are still people today who can claim samurai lineage, there are no special privileges afforded to them per se. In the late 1800s some ex-samurai didn’t take this well, and there were a series of conflicts, culminating in the Satsuma Rebellion of 1877 that ended the samurai as a recognized social class. The samurai became a page in Japan’s history, and the march of progress continued.

The concept of Bushido (the “Way of the Warrior”) and its supposed code of honor, which put samurai under intense pressure to be honorable or commit seppuku, came from Inazo Nitobe, who wrote a book in English called Bushido: The Soul of Japan, in an attempt to rehabilitate Japan’s image in the West. Although a Japanese man born in Japan, he admired Western culture to the point where he was highly fluent in English, converted to Christianity, and married a Caucasian woman. While he apparently had some genuine expertise when it came to English-language literature, he was comparatively ignorant of Japanese history.

Since information about Japan was so scarce in the early 1900s, his book was nonetheless a huge success and people took it as fact. Actual historians in Japan wrote scathing critiques, calling out the book’s blatant historical inaccuracies. The notion of “Bushido” as he defined it simply didn’t exist in Japan before that, and Nitobe’s conception of it was at least as much Christian as Japanese, having been created to appeal to Westerners in the first place by way of equating honorable samurai with virtuous, chivalrous knights. (The notion of a chivalric code that knights followed was itself a result of mythologizing in folklore and literature in the first place.) Western media, whether James Clavell’s Shogun or the film The Last Samurai, uncritically portrayed his version of the samurai ethos, which the likes of Gygax also internalized and spat out in the form of Honor rules.

That might have been the extent of Nitobe’s influence, but in the early 20th Century the modernizing Japan was flexing its military might, fighting and winning wars against other Asian counties and even Russia. This was when Japanese nationalism took hold and the military—which at the time was highly independent of the civilian government—became a hotbed of extremism. It wasn’t unusual for nationalists to assassinate civilian politicians who weren’t sufficiently behind the military’s imperialist projects in Asia.

In the buildup to Japan’s entry into World War II, the Bushido myth proved an effective propaganda tool to encourage Japanese troops to become fanatics for the cause. Katanas were a powerful symbol of national pride, even though the mass-produced ones handed out to Japanese officers represented a nadir in Japanese sword making. The Imperial Japanese military’s evil deeds weren’t totally unique in human history, but they were nonetheless unspeakable, solidifying the anti-Japanese sentiment that persists across East Asia today.

In the postwar years, the Japanese psyche dealt with the nation’s defeat—and especially the atomic bombings—in a variety of ways. There was a great national shame, some voices proclaiming that Japan could reinvent itself as a new force for peace and progress, and of course some ultranationalists who cling to that murderous ideology to this day, just as there are still fascists and their ilk in the West. While you occasionally get a manga or light novel from a creator who’s into Japanese nationalism, by and large Japanese narratives about the samurai, although idealized to be sure, don’t have anything like the caricature seen in Western media.

Historical accuracy is hard to achieve even for historians, much less game designers. History is ultimately a story we’ve constructed to explain the past. When we do it ethically, we do what we can to have that story reflect the available evidence, but honest history will admit where we simply don’t know what happened. Future historians who try to untangle the moment we’re currently living through may have an astronomical quantity of tweets to sift through, but if you go far enough into the past, you reach eras from which we just have scant collections of pottery. For lay people, primary sources are often arcane or boring, and we get out view of history from simplified lessons and pop culture. To some extent that’s unavoidable, but it does open us up to propaganda like 300, a film that historians knowledgeable about the era in question would find at turns laughable and sinister.

In science education there’s a concept called “lies to children.” It’s essentially the idea that you have to teach a version of things that isn’t exactly right in order to make it simple enough for young learners to get enough of a footing to be ready for the real thing. Atoms don’t have electrons going around in neat little orbits like in the picture in an elementary school textbook, but your average 3rd grader isn’t anywhere near ready for a lecture on quantum mechanics. History is another subject that can easily get deeper than laymen have the time or knowledge base to comprehend. Replacing the numerous and disparate threads of history with easily digestible stories seems unavoidable to some extent, but we need to be more careful about the stories we choose to tell ourselves as a society. We still have people trying to defend the lionization of Christopher Columbus for example, even though he somehow managed to be a vile person even by the standards of 15th Century Genoa, which is saying a lot.

Role-playing games are vehicles for us to gather to enter worlds of our own imaginations, and in practice you have to have a consensus about the fiction world in question among a small group of people. That makes them naturally work against true historical accuracy, though for that matter it similarly makes it hard to get a group together to play a licensed game unless everyone is on board with the licensed property in question. When I say I want “authenticity” in an Asian setting for Dragon World (and Asian settings in TTRPGs in general), I don’t mean rigid conformity with history, but I do what something where someone from the cultures in question wouldn’t feel insulted or roll their eyes.

The colorful ninjas of Naruto have virtually no connection to the historical spies—though the ninja likely encouraged fanciful myths about themselves—but it reflects a native’s knowledge of Japanese culture and mythology, and is richer for it. D&D’s attempts at ninjas fall into the “guys in black pajamas” stereotype beloved by Cannon Films, and lack the bonkers fun you get from things like ninjas summoning giant supernatural frogs. Not every source of inauthenticity will lead us on a journey that includes discussing hideous war crimes (seriously, even at the heights of imperial fervor Japanese civilians were still shocked at what their military was up to in Asia), but there’s inevitably something deeper and more interesting, such that even if we were to set aside questions of what is respectful (which we shouldn’t), we’d still be missing out.

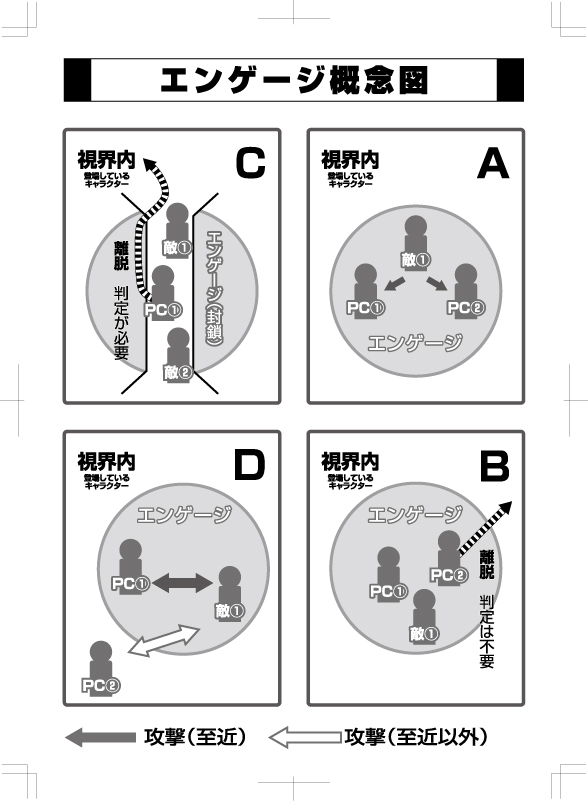

I wound up getting a copy of the Advanced Rulebook (上級ルールブック) for

I wound up getting a copy of the Advanced Rulebook (上級ルールブック) for

I now officially wish I’d gotten this game sooner.

I now officially wish I’d gotten this game sooner.