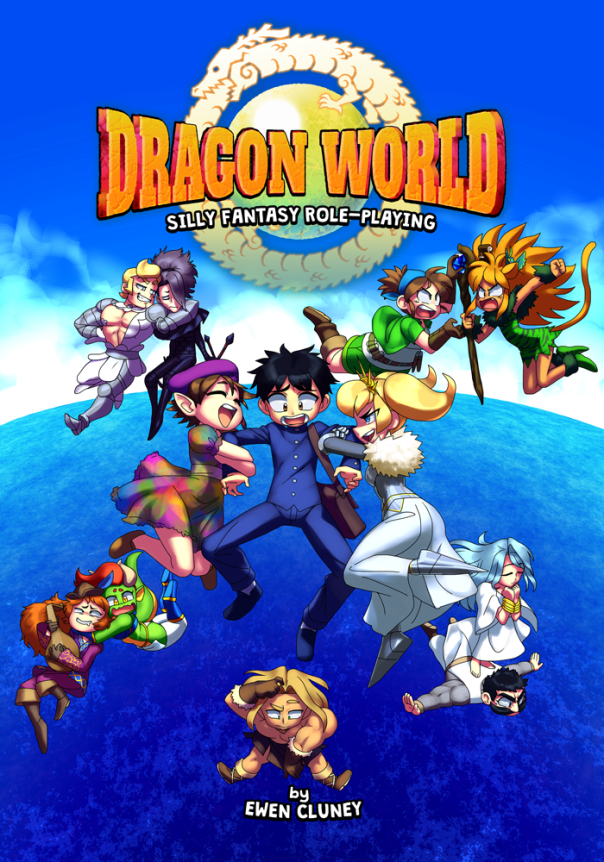

Dragon World is a Powered by the Apocalypse RPG for fantasy comedy adventures in the vein of classic anime like Slayers and Dragon Half. The game has been in the works for a while now, and we’re now gearing up to launch a Kickstarter some time in the next few months.

Dragon World Hack 0.4

Dragon World Playbooks

I had the idea for Dragon World when I finally got my hands on the Dragon Half manga. (Which BTW is finally getting an English language release from Seven Seas.) In anime there was a weird trend in the early to mid-1990s of making short direct-to-video adaptations of much longer manga, which in turn sometimes wound up being the only versions that made their way to the English-speaking world. Dragon Half started as a 7-volume manga (later re-released in a 3-volume “omnibus” edition, which the English version is based on), which could’ve worked nicely as a full 26-episode TV series. Instead it got a mere two OAV episodes, and plans to do two more episodes got scrapped. The Dragon Half OAVs had a little bit of a cult following in the early anime scene, and I devoured the manga once I got my hands on it. It shows its age and anime-ness with a lot of fanservice (our heroine pretty much only wears a metal bikini), but the zany humor, flagrantly ridiculous take on the fantasy genre, and Ryusuke Mita’s energetic art make it worth your time.

That wasn’t too long after I’d discovered Apocalypse World, and as I made my way through the manga, I kept seeing it in terms of different AW-style moves and their outcomes. This was before the term “Powered by the Apocalypse” came about and while it was still the thing to have those “AW hacks” end with “World,” so “Dragon World” was born. A certain portion of anime and manga, especially from the 90s, used “dragon” in titles to essentially signify “fantasy,” probably a result of Dragon Quest being so massively popular and influential, plus it was a tongue-in-cheek nod to Dungeon World. (And I did talk Jonathan Walton into making a game called “& World.”) From there I watched a ton of Slayers (probably the single most popular comedy fantasy anime), and a bunch of others, giving me a wider palette of ideas to draw on. Dragon World most blatantly shows its influences in the selection of classes, ranging from the likes of the Explosive Mage and Dumb Fighter (which have Lina and Gourry from Slayers at their core) to the Angsty Shadow Warrior (for whom Dororo from Sgt. Frog was an inspiration, but also a bunch of fantasy tropes) to the Shiny Paladin and Ruthless Warlord (who come from silly takes on D&D classes). One of my favorites is the Chosen Visitor, which is a Japanese teenager sent to this fantasy world and given weird powers, echoing shows like Magic Knight Rayearth and El Hazard.

This is the fourth version of Dragon World that I’ve shared with the world, and it’s generally been through a lot of revisions as I did a bunch of playtesting and figured out what did and didn’t work, and thought of new stuff to add. The game started considerably closer to Apocalypse World, but I dropped things like highlighting stats and marking experience. On the other hand (although I refined it a bit), the concept of replacing Harm with “falling down” remained a core part of the game from the start. I changed the selection of classes a little, adding the likes of the Ruthless Warlord and changing the Useless Bard into the Foolhardy Bard (which was how people had been playing the Useless Bard for the most part anyway).

It’s not in the Hack, but the final commercial version is going to have a setting chapter for the land of Easteros. (Not the only Game of Thrones reference in there, but there’s copious anime nonsense regardless.) It was generally an opportunity to put together a bunch of toys and plot hooks, plus some dumb humor (like a pun-laden list of 100 slime names).

In any case, I’m looking forward to finally bringing this game fully to fruition in a nice book with actual artwork, and possibly putting together some supplements and alternate settings. I’m also planning a Creative Commons release, in the hopes that (not unlike with Dungeon World, though presumably in much lower quantities) people will take the opportunity to design and publish their own Dungeon World weirdness.